f/7.1, ISO 400, 1/100, 100mm macro lens

A Goldenstar (

Erythronium rostratum) in its full glory. This is one of Ohio's rarest plants and is essentially known from only one giant population in the Rocky Fork valley of western Scioto County. A much smaller population was discovered in fairly recent times a few miles to the west, in Adams County.

About every time I post photos of this species, people let me know that they have "Goldenstar" growing in their yard or local park. Not so. They are seeing the superficially similar Yellow Trout Lily (E. americanum), which is common and widespread. Goldenstar has a very patchy distribution with isolated populations far removed from its Ozarkian strongholds.

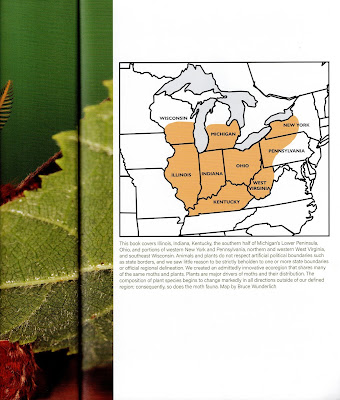

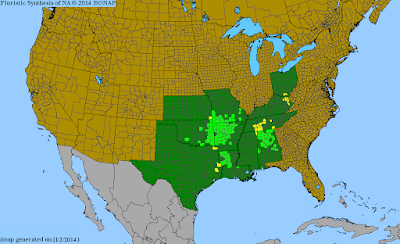

Goldenstar Distribution. Map courtesy of

BONAP

Green counties indicate that the species is present and not rare; yellow indicates it is present but RARE. The northeastern Kentucky and southern Ohio populations are far removed from the core range.

Back to the Goldenstar image above. The plant was growing between projecting buttresses of an American Beech (Fagus grandifolia) trunk. There were myriad potential subjects at this site but this one especially caught my eye as beech are a common associate in the rich woodlands favored by Goldenstar. The gray elephant skin bark of the trunk made a nice backdrop, and the senescent beech leaves are a nice touch. For this image, I used a common (for me) aperture of f/7.1 to softly blur background features and put the emphasis on the extraordinary flower. There were breezes on this morning, so I elevated the ISO to 400, and that gave a shutter speed of 1/100 - fast enough to freeze any slight wind-induced tremor. I'm trying to time shutter actuations with calm periods, of course.

%20copy.jpg)

A wide-angle lens (Canon 16-35mm f/2.8 II) is nearly always with me when I hunt flowers. It is incredibly useful for showcasing overall habitats. For this shot, the camera was on my mini-tripod, essentially flat on the humus. The lens is around eight inches from the flower - at its minimum focusing distance - showing how ultra-wide the reach of a lens like this is.

Goldenstar favors beech-maple forests with plenty of leaf litter and is often on steep slopes. This image presents very typical habitat for the rare lily, at least insofar as the Ohio sites go. This is a case where stopping down is effective, and the camera parameters were f/16, ISO 400, at 1/100 second. The lens was at 16mm for maximum spread. In my opinion, wide-angle lenses are an essential component of the ecological photographer's tool bag. They permit more of the story to be told.

f/9, ISO 250, 1/50, 100mm macro lens

A photogenic trio of Snow Trillium (Trillium nivale). Odd numbers can be quite appealing in regard to subjects. and I do typically find my eye more drawn to 3's, 5's, 7's etc. This group caught my eye from afar and I wouldn't have missed photographing them. This odd-even thing has even been quantified as the wonderfully named Rule of Odds. The RoO states that compositions with an odd number of subjects or elements will be more dramatic than a composition of an even number of subjects.

Pairing is common in our human bodies: two eyes, ears, hands, legs, arms, etc. The theory goes that when we look at something with odd numbers, the brain has more difficulty in grouping them, that something somewhere is leftover, and your brain commands your eyes to continue sweeping over the composition to find the "missing" part.

I don't know about all of that, but there does indeed seem to be to be an allure to the odd that makes us want to study odd-numbered subjects in greater detail than even-numbered ones.

Here's a very similar trio of Snow Trillium, with a slight tweak from the above image. As with the prior image, my ISO was at 200, but I stopped down to f/14. The tradeoff with smaller apertures is a diminishment of light entering the camera, which is mitigated by a slower shutter speed, 1/20 of a second in this case. By keeping the shutter open longer, the camera can harvest the same amount of light as it did when the aperture was a more open f/9 and thus could collect adequate light more rapidly - the prior shot was at 1/50. As there was no wind at this point in the early morning, I didn't care how slow the shutter speed was - it was essentially irrelevant.

As my camera was fairly close to the subjects, the depth of field was reduced. By moving the camera farther away, depth of field increases but so will your need to crop the image to make the same composition as shown here. So, to get a more depth I just shut down one and two-thirds stops to f/14. The background was not particularly cluttered or distracting so I wasn't too concerned about that. If you scroll up to compare with the prior image, you'll see that the rear flower is softer. To me, either image looks fine, but I probably prefer the f/14 shot above.

It's good practice, especially early on, to take images of the same subject with a range of apertures, to become familiar with the effects caused by aperture adjustments.

f/10, ISO 200, 1/60, 100mm macro lens

In spite of the Rule of Odds, I won't hesitate to fire away at evens. For a few minutes, the early morning light caused this pair of trilliums to glow, while the backdrop remained largely dark. It was incredibly alluring and I'm glad I happened to be there for their brief moment in the spotlight. I suppose the situation might have been even cooler had there been three (or five), but there wasn't. As with some prior shots, I stopped down a bit more to bring additional focus to the rear plant, especially as there were no background distractions. In hindsight I would have taken an image at f/16, too.

f/7.1, ISO 250, 1/50, 70-200mm lens at 175mm

Another violation of the Rule of Odds, but what good are rules if they can't be violated? This ensemble of trillia was too good to pass by. They festooned an otherwise barren limestone ledge, almost as if they were purposefully planted there. I like the exposed limestone, as

Trillium nivale is very much a calciphile, or limestone lover. This shot was handheld, using my Canon 70-200mm f/2.8 II lens. The plants were in a hard area to set up a tripod on, but that lens has superb image stabilization and is easy to handhold and get sharp shots at slow shutter speeds, even slower than the 1/50 used here. Normally I'll always use a tripod if circumstances permit, though. And as an aside, I always try to remember to turn off the image stabilization on stabilized lenses when they are mounted to a tripod. If turned on, the image stabilization can lead to an effect called a feedback loop when tripod-mounted and that can lead to blurred images. Yep, just one more thing to remember.

%20copy.jpg)

f/7.1, ISO 200, 1/60, 100mm macro lens

I'm back in compliance with the Rule of Odds here, if only a solo subject. The petals of this Snow Trillium are already blushed with pink, a sign of aging. The flower will soon wither away. By now, just a week later, many of the thousands of trilliums in this population will be tinged with pink and it won't be long before the flowers are gone. This site, by the way, is accessible. It is the

Arc of Appalachia's Chalet Nivale Preserve in northeastern Adams County, Ohio, and it isn't a tough place to get around. While you may have missed the show this spring - unless you get there fast - there's always next March.

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)