Fourteen bald eagles were tallied on the count, a record high/Jim McCormac

Nature: Record highs and unusual sightings turn up in annual Christmas Bird Count

NATURE

Jim McCormac

The annual Christmas Bird Count (CBC), run under the auspices of the National Audubon Society, took place from Dec. 14 to Jan. 5. Well over 2,500 counts are conducted throughout the U.S., Canada and many other countries.

One of the oldest counts is the Columbus CBC. The inaugural count took place on Dec. 26, 1913, conducted by one observer. Fourteen species and 179 individuals were tallied. The count came nine months after the worst flood in Columbus history, which may have accounted for the low turnout of birds and birders.

The Columbus CBC was intermittent from 1913 to 1954. Since then, not a year has been missed and the last iteration took place on Dec. 19, 2021. Rob Thorn has served as compiler for over 20 years, and it’s a big job.

Thorn recently sent along a summary, and the 2021 count was one of the most productive ever. He marshalled the efforts of 88 observers. Only once has the count had more participants — in 2012, when 89 people helped.

The count area is a 15-mile diameter circle centered on Cassady and 5th avenues on the East Side, and that’s a lot of turf to cover.

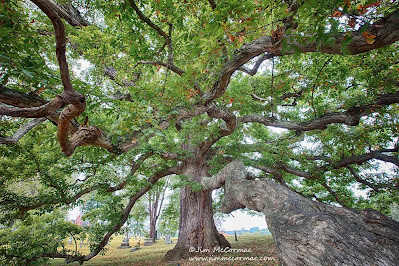

Bernie Master, Tim Fitzpatrick and I covered a section of the South Side, including the sprawling Green Lawn Cemetery and the Columbus Impound Lot. We added a few goodies to the total, including merlin (a type of falcon) and fox sparrow.

A whopping 86 species were found, which has been eclipsed but once, also in 2012, when 89 species were counted. Many record high counts and unusual species turned up, and I’ll mention some below.

Seven

trumpeter swans were found, a record high. This species was introduced (some say reintroduced) to Ohio in 1996 and is flourishing. Also in the fowl department, a blue-winged teal was exceptional. It is our least hardy duck and very rare in winter.

Red-shouldered hawks continue to expand, and a record count of 15 was made. Bald eagles also continue their meteoric increase. The 14 found was a record, but one that I predict is soon broken.

Eastern bluebirds, to the delight of many, also are doing well. A best ever 142 birds turned up. This gorgeous thrush has adapted well to suburbia. Less known is the elusive hermit thrush, but intrepid observers located nine of them. It might be a while before that total is bested.

Incredibly, four warbler species were documented. The only expected species is the rugged yellow-rumped warbler, and 49 were found. Completely unexpected was a

black-throated green warbler, orange-crowned warbler, and two palm warblers. The latter three should be in the southern U.S. or even farther south.

A blue-gray gnatcatcher was a surprise. The spritely insectivore has been found on only six prior counts, the last in 2012.

Massive citizen science projects such as the Christmas Bird Count provide a wealth of data regarding avifauna. Some of the trends are negative, and some positive.

Up until 1970, double- or triple-digit numbers of northern bobwhite were found on every Columbus count. After that, few of the charismatic quail were located. Eight on the 1985 CBC were the last recorded. Bobwhite are victims of rampant development and wildlife-unfriendly agricultural practices.

On the other hand, opportunistic ring-billed gull numbers are soaring. Only single- or low double-digit numbers occurred in the count’s early years, if they were found at all. Gull numbers began to explode in the early 1990s, and counts have averaged 1,700 birds over the last 15 years. Our artificial lakes, reservoirs and prodigious human garbage have benefited the adaptable omnivores.

Thanks to Rob Thorn for his hard work and years of CBC stewardship, and to all of the count participants for their contributions.

Naturalist Jim McCormac writes a column for The Dispatch on the first, third and fifth Sundays of the month. He also writes about nature at www.jimmccormac.blogspot.com.