A northern saw-whet owl rests in the hand of Blake Mathys, just prior to its release/Jim McCormac

Nature: Investigating the northern saw-whet owl in Ohio

November 19th, 2023

NATURE

Jim McCormac

Lots of interesting and little-known creatures emerge under cover of darkness. Some of them are human, but most are not. Perhaps foremost in piquing human interest about animals that ply their trade after nightfall are the owls.

Owls have long been a source of fascination to us. Athena, the mythical Greek Goddess of Wisdom, was smitten with owls and held them in high regard. A genus of owls, Athene, is named for her. It includes the North American burrowing owl, Athene cunicularia. In 1994, ancient art was discovered adorning the walls of Chauvet Cave in France. Some of this work depicts owls, and was created over 30,000 years ago. Effigy pipes depicting barred owls – a common Ohio species – created by Hopewell Indians date to around 100 B.C. and have been found in Tremper Mound in southern Ohio.

A local owl aficionado is Blake Mathys, a biology professor at Ohio Dominican University. He established the

Central Ohio Owl Project (COOP) in the fall of 2020. I wrote about COOP and its goals in a February 7, 2021 column. One of his major study targets is one of our most charismatic little hooters, the northern saw-whet owl.

Mathys, who lives in Union County, bands saw-whet owls on his property each fall. A string of mist nets is placed in a wooded opening, and saw-whet calls are broadcast from a nearby speaker. Owls investigating the calls fly into the nets and become entangled. The soft mesh causes no harm, and captured birds are quickly extracted.

Netted owls are taken to the “lab,” a nearby table where each bird is measured, weighed and feather details are studied to determine age. The latter process involves shining ultraviolet light on the owl’s underwings. Newer feathers are infused with a compound known as porphyrin, which glows fluorescent pink under UV light. With experience, the bander can accurately assess the bird’s age by its pinkness or lack thereof.

Perhaps most importantly, a lightweight aluminum band is placed on a leg. The band sports a unique number and allows positive identification if the bird is recaptured. An enormous amount of information regarding bird migration, seasonal movements and longevity has been amassed by banding. In the case of northern saw-whet owls, most of what we know is the result of efforts by banders such as Mathys.

I was fortunate to be part of an assemblage that visited Mathys’ banding operation on the night of November 11. A nip was in the air as darkness fell, and it was downright chilly when we made the first net check. Nothing. Brief disappointment ensued but that was offset by optimism for upcoming net runs. Sure enough, we were elated to see two saw-whet owls in the nets on the second check.

Both birds turned out to be hatch-year females. They would have been born in spring or early summer, and probably WAY north of where they were caught. The vast majority of saw-whet owls breed in northern forests across Canada and the northern states, from Alaska to New England. There are only two recent Ohio nesting records, from Erie and Huron counties along Lake Erie. At one time, the owl was a more frequent nester in northern Ohio.

Most of the people present this night had never seen one of the wee owls and were thoroughly enchanted. A big one – females are larger – weighs around 100 grams, or the same as 15 quarters. They measure but 8 inches in length, with a wingspan of a foot and half. In contrast, our largest owl is the great horned owl, and it tapes out at nearly 2 feet in length with a 4-foot wingspan and body weight of 3 pounds.

Northern saw-whet owls are incredible nocturnal hunting machines. Their eyes constitute nearly 5% of the body mass and have many more cones than human eyes. This allows them to see in darkness with amazing accuracy. Large offset ears permit fine-tuned sound triangulation. Woe to the scurrying rodent, even if it’s under vegetation. Flight feathers edged with comb-like extensions allow for silent flight, and once a pounce is made, the owl seizes its victim with powerful talons from which escape is impossible. I would note that the first thing someone usually says upon clapping eyes on a saw-whet owl is “cute”. Many mice and voles would strongly disagree.

Blake Mathys has captured nine saw-whets this fall, and more will undoubtedly follow. Last fall he caught a remarkable 34 birds. Kelly Williams, a bander working with Tom Bartlett on Kelleys Island, caught 16 owls on the same night we were out. Bartlett has captured over one thousand in his decades of banding on the Lake Erie Island, demonstrating that the owls migrate across the great lake.

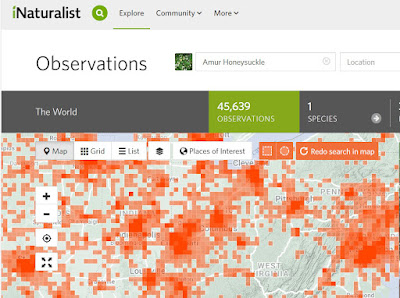

The work of Mathys, Bartlett, Williams, Bob Placier (who bands saw-whets in Vinton County) and others have illuminated the frequency of this owl. During migratory periods, and probably in winter, the little owl is probably the most common owl of the seven (eight, if snowy owls are present) species in Ohio.

Naturalist Jim McCormac writes a column for The Dispatch on the first, third and fifth Sundays of the month. He also writes about nature at www.jimmccormac.blogspot.com.

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)