A romp through the diverse flora and fauna of Ohio. From Timber Rattlesnakes to Prairie Warblers to Lakeside Daisies to Woodchucks, you'll eventually see it here, if it isn't already.

Friday, January 27, 2023

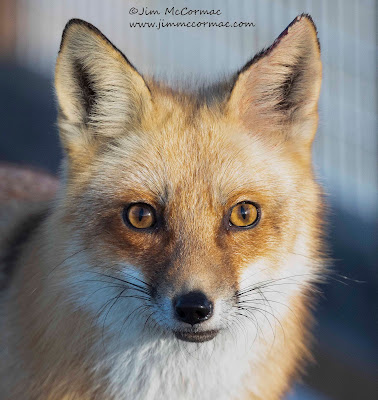

A fox at Cape Henlopen

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

A snowy wonderland

Last Sunday, January 22, 2023, dawned cool and crisp, with the world covered in a gorgeous veneer of soft fluffy snow. Such scenes are not to be missed, especially around here when pure winter days are a rarity. Time is usually of the essence as soft snowy cloaks like this are typically ephemeral and begin melting by midday or so. I rolled out early and only had to head five minutes away, to a section of older-growth riparian woodlands along the Olentangy River in Worthington, Ohio.It's hard to make much progress - as if that matters - when the landscape looks like this. Every new position and turn of the head offer interesting perspectives. I tend to dawdle along, looking for inspiration and love trying to capture interesting scenes with my camera.

Saturday, January 21, 2023

A hodgepodge of pics

I haven't had a lot of time for blogging of late, nor have I been afield much. A number of tasks have gotten in the way, but that will all change soon, with a trip to Delaware Bay. Seals are a primary target, but there is much else of interest to look forward to.

In dredging the photo vault for stuff in recent days, I've run across a few plums (at least to me), and share a few of them below.

Male Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythropthalmus) in a briar patch. Shawnee State Forest, Scioto County, Ohio, November 23, 2022.Glorious Habrosyne moth (Habrosyne gloriosa), Highlands Nature Sanctuary, Highland County, Ohio, July 17, 2021. One of scores of species of moths seen during Mothapalooza.Wednesday, January 18, 2023

Gardening for Moths: A Regional Guide

We worked with Ohio University Press to produce this 280-page book, which features over 500 color photos and profiles nearly 150 heavy-hitter native plant species and about the same number of moth species. It covers a region that includes nine midwestern states, or parts thereof. A meaty introduction makes the case for moths' importance in food webs, such as for bats and birds. Moths play a large role in pollination services - certainly far beyond that of butterflies, which they greatly outnumber in both species and sheer numbers. Other introductory material covers moth myths and reputation, moth-watching tips, moth photography, human impacts on moths and moth conservation and much more. The text is peppered with numerous inset boxes that feature cool mini-stories about moths: aquatic moths, moth-specific ear mites, bolas spiders that lasso moths, moth caterpillars, moths and goatsuckers, moth-bat warfare, and other interesting material.

The overarching idea with this book is to shine a light on a facet of natural history that normally remains in the dark and is quite poorly known to most people. Gardeners, collectively, have tremendous power to influence our environment for the good, and this book offers a path forward by helping a charismatic group of insects of inestimable importance to the natural world.

For a description of Gardening for Moths, see the Ohio University Press page, HERE. Books can be pre-ordered there, or at Amazon, RIGHT HERE.

Monday, January 16, 2023

Nature: Crafty herring gull impresses with problem-solving skills

Nature: Crafty herring gull impresses with problem-solving skills

January 15, 2023

Jim McCormac

A point of avian trivia: Only one state eclipses Ohio in the number of gull species seen within its boundaries. It is California, which dwarfs Ohio in size and has 840 miles of Pacific coastline. Twenty-seven gull species have been recorded in the Golden State.

Ohio lags California by only six species, with 21 gulls so far recorded. That gap will soon narrow, once new records of common gull (a European vagrant) and glaucous-winged gull (from the West Coast) are formally accepted. These vagrants were found in late December and early January on the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland – one of North America’s great gull hotspots.

The default gull in Ohio is the ring-billed gull. This is the species that roosts in mall parking lots, forms flocks on the Scioto River and local reservoirs, and scavenges scraps in McDonald’s parking lots. Occasionally, noticeably larger birds intermingle with the flocks. These are herring gulls, another common gull in Ohio, especially along Lake Erie.

Gulls are intelligent, long-lived, highly adaptable, and situationally aware, with a penchant for doing interesting things. Perhaps no gull out-gulls the herring gull. The big birds are well-known for their cleverness, and ability to solve problems.

As herring gulls spend most of their lives around water, they routinely encounter mussels. Mussels, or clams, are hard-shelled bivalves and - when sealed up - are, in essence, living rocks. It would require a hammer to crack most of them open. The reward for doing so? The meaty animal inside, a gull delicacy if there ever was one.

Clam-cracking is a true problem if you are a herring gull with no hands, hammers, or chisels. But somewhere along the line, the gulls learned about succulent protein and vitamin-rich clam meat and devised a clever trick to open clams.

On a recent trip to Edwin Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, in the shadow of Atlantic City, New Jersey, I had the opportunity to photo-document herring gulls opening blue mussels. These bivalves are common in Reeds Bay on the south side of the refuge.

Ages before Isaac Newton watched an apple fall from a tree, leading to his “discovery” of gravity, herring gulls had learned to put gravitational pull to work. Hungry gulls would fly out to Reeds Bay, locate a blue mussel bed, and pluck a clam from its watery home. The hunter would then fly back to a refuge road of hard-packed gravel, and hover over it. From a height of several stories, the gull would drop the mussel like a feathered B-24 delivering a bivalve bomb.

The hapless clam would freefall toward an explosive doom, the gull flutter-dropping after it. Upon impact with the roadbed, the hard shell would shatter to smithereens and the gull would quickly seize the now-available meaty morsel. Speed was critical on the part of the hunter, as other clever but perhaps lazier gulls lurked nearby, ready to usurp the hard-won handiwork of the legitimate heir.

I’ve seen such tactics used by herring gulls numerous times in many places, including along Lake Erie. Many other gull species do this as well, including our common ring-billed gull. While this experience is, I’m sure, not fun for the clam, it is interesting to watch.

The oldest known herring gull lived to age 49, but we know little about gull longevity. As the global population is around a million birds, there are certainly older individuals, possibly even centenarians. An old clam-cracking gull has probably flexed a lot of mussels in its time.

Naturalist Jim McCormac writes a column for The Dispatch on the first, third and fifth Sundays of the month. He also writes about nature at jimmccormac.blogspot.com.

Saturday, January 14, 2023

Red-tailed Hawk eats Gray Squirrel!

Eventually the hawk got to the head and commenced eating the nose - another delicacy? In this image it has deftly grasped the squirrel's eyelid. Raptors deal with prey like this with surgical precision, using the bill like a scalpel and manipulating and repositioning the prey with those large powerful feet and talons. They are more efficient than most people would be with fork and knife.

If nothing interfered, I'm sure the bird left little but fur and bones. Almost nothing goes to waste. My only regret - and it isn't worth regretting as there is nothing one can do - is that the day was a typical gray leaden Ohio winter day. Light was abysmal as it is so often around here in winter, and it only deteriorated as heavy cold rains moved in. How these scenes would have popped in golden morning sunlight! Ah well, I count myself lucky to have had a ringside seat to a dining Red-tailed Hawk. He was still there feeding away when we departed.

Here's a brief video of the red-tailed feeding. I was hoping that the snaps and cracks of tendons and muscles separating would come through, but the camera didn't seem to pick those up. I could hear it, though, and the sound effects added interest to the experience.

Saturday, January 7, 2023

A tale of two hawks

As always, click the photo to enlarge

An adult Red-shouldered Hawk (Buteo lineatus) sits on a wire in the little village of Limerick, in Jackson County, Ohio. I was here on December 29 to cover my turf for the Beaver Valley Christmas Bird Count, along with BWD (Bird Watcher's Digest) editor Jessica Vaughn. By the way, BWD is a great magazine and if you have an interest in birds, you should subscribe. Not to toot my own horn although I clearly am, but I have an article on Kankakee Sands in northwest Indiana in the current issue. It's a spectacular birding locale and I've written about Kankakee a number of times on this blog. The recent revamp and reissue of the magazine resulted in a physical size increase, which much better showcases the numerous excellent photos featured in each issue.Anyway, we did well on the count, with 45 species, including two Eastern Phoebes. I find these tough little flycatchers about every three to five years on this count. If the weather gives them half a chance, they'll try to ride out the winter. The bird in the above photo was one of six Red-shouldered Hawks that we found, and it was sitting in clear view of an active feeder behind a church. Despite its presence, the songbirds were not overly deterred from hitting the feeders, although I'm sure they kept a close eye on the raptor. Red-shouldered Hawks routinely visit my yard, with its usually busy feeders. "My" birds react much the same. Activity carries on, the soundscape is awash with the regular calls, birds continue to hit the feeders, and bold little chickadees will fly right by the much larger raptor as it sits on the fence or a low limb of the walnut tree. The comparatively slow and cumbersome hawk would stand little chance of bagging speedy songbirds, and they know it. I must admit, Red-shouldered Hawks have a soft, rather cute appearance that befits their mellow (for a raptor) persona. Chipmunks, mice and shrews beware, though - they form a large part of Red-shouldered Hawks' diets. In warmer seasons, the raptors catch lots of amphibians and reptiles. I imagine my red-shouldered visitors are mostly watching for chipmunks and the occasional Short-tailed Shrew that dashes from cover for spilled seed.

A juvenile Cooper's Hawk perches in my backyard yesterday morning. These bird hunters are near daily visitors, and I often know when they are around without even casting eyes on one. The yard falls silent, and songbirds vanish. They know to take no foolhardy chances with a Cooper's Hawk, whose bread and butter is small birds.Monday, January 2, 2023

Nature: Delicate frost flowers are Nature's answer to ice sculptures

Nature: Delicate frost flowers are Nature's answer to ice sculptures

January 1, 2022

Jim McCormac

Saturday, Nov. 19 dawned crisp and cold. I had stayed at the Shawnee Lodge in Shawnee State Park (Scioto County) the preceding evening to attend a meeting. The largest contiguous forest in Ohio, Shawnee State Forest, surrounds the lodge, and there are about 70,000 acres of wildlands to explore.

I left the lodge before the crack of dawn. Within a minute of departing, I was pleased to see a gray fox saunter across the road. Gray foxes have become much scarcer in recent decades, making sightings of these superb cat-like canids especially noteworthy. Perhaps the elegant fox was an omen of good things to come.

My primary mission, however, involved inanimate objects known as frost flowers. For many years, I had heard about these icy ephemera but had yet to clap eyes on one. Today would be the day.

The day before had been fairly warm, with temperatures in the mid to high 30s. Scattered rains in the preceding days had dampened the ground. When I headed out in the morning, the temperature had plummeted to 12 degrees. The conditions were ripe for the formation of frost flowers.

A frost flower is an incredibly delicate ice sculpture that forms around the bases of certain plants. In southeastern Ohio, the primary producer of frost flowers is a little mint called dittany (Cunila origanoides). It is common in Shawnee State Forest.

I headed for a remote ridgetop with well-drained sparsely vegetated slopes - perfect dittany habitat. I knew from experience that dittany abounded at this site. Within seconds of arrival, I saw what looked to be shards of whitish Styrofoam dotting the ground. Finally – the fabled frost flower!

While frost flowers don’t look like much from afar, up close they are spectacular. Wafer-thin icy curlicues resembling ribbon candy cling to the bases of the dittany stems, forming all manner of sculptures. No two are alike.

One must be gentle around frost flowers. I quickly learned, when trying to pull intruding vegetation aside, that even the mildest perturbance would shatter the frozen rime. The observer must look, not touch, to avoid instant destruction.

Frost flowers form when mostly senescent host plants are still drawing water upward into the stem. Cold air freezes the liquid in the stem, creating longitudinal fissures. New water is forced from these cracks, creating the fantastic icy artwork.

The first cold snaps of mid- to late November is prime time for frost flower formation. Not all suitable plant hosts will form them the first frosty night, so seekers might have a few shots at finding the icy “flowers." Searchers need to get out early. The first sun rays quickly melt the frozen objets d’art.

Adventurous gardeners might consider planting a frost flower garden. In addition to dittany, other native (or nearly so) Ohio flora known to produce frost flowers are Canada frostweed (Helianthemum canadense), white crownbeard (Verbesina virginica), and wingstem (Verbesina alternifolia).

Canada frostweed will be tough to find in the nursery trade. The delicate little member of the rockrose family isn’t common garden fare. The other two are easily obtained, but purists can take note that although the southern white crownbeard occurs as far north as northern Kentucky, it hasn’t been documented as a native in Ohio.

As the morning warmed and the frost flowers liquefied, I moved on to other photographic pursuits. And lo and behold, around 10 a.m. I spotted and photographed a female bobcat with two kittens. They were the subject of my Dec. 4 column.

Apparently, that gray fox was indeed a good omen.

Naturalist Jim McCormac writes a column for The Dispatch on the first, third and fifth Sundays of the month. He also writes about nature atwww.jimmccormac.blogspot.com.

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)